This vendible has been sponsored by Central Square Foundation.

“I love colouring, connecting the dots in my workbook, and learning to count using marbles. Mathematics is my favourite subject,” says Darpan Malaviya, a Class 1 student from the primary school in Kodiya Chhitu village of Sehore district in Madhya Pradesh.

Darpan’s school is one of the many primary schools in India where there has been an enthusiastic stir in the public education system. Central Square Foundation (CSF) has been working to empower children with fundamental literacy and numeracy skills while ensuring the right wordage of the curriculum — as per NIPUN Bharat Mission guidelines and State Education boards’ framework.

Founded in 2012, Central Square Foundation is a non-profit organisation, working to transform the Indian school education system by improving the learning outcomes of all children, primarily from low-income communities.

CSF’s work is mainly focused on four impact areas — Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN), EdTech, Affordable Private Schools, and Early Childhood Education.

“We are currently working in well-nigh 12 states wideness India, and in most states, we have other education-partner NGOs like Room To Read (RTR) and Language and Learning Foundation (LLF), who work on developing programmes designed to support both children and teachers,” says Anustup Nayak, project director at CSF, in conversation with The Largest India.

He says they work with their technical education partners to modernize the quality of the diamond of their programmes. “We squint at global weightier practices and consider the good examples that we have produced ourselves to see whether the teachers can largest use these programmes. So, we squint into the material with these lenses and see if it is simple and easy to understand. We basically modernize the user interface of the programmes for the teachers and students.”

Coming to the implementation of these programmes, he says, “Most programmes are well-designed, but struggle at the implementation phase. So, we go on the ground, sit inside the classrooms, observe teacher training programmes, and understand what is working in the implementation phase and what needs to be improved. We then provide feedback to modernize the programme design.”

Anustup shares how their team is like a thought partner to their tech partners. “We moreover sit together with them whenever we are jointly advocating any wonk strategy to the government.”

Teachers form the windrow of an educational system

To unzip its vision of ensuring quality school education for all children in India, CSF works very closely with the teachers to ensure that they are well-equipped with the right techniques, right tools, and the right training.

“When teaching children the nuts of language vanquishment or mathematics, there are unrepealable scientifically proven techniques. For example, if you want to teach children numbers, it’s largest to get them started with practical hands-on models. In our programmes, children unquestionably touch physical objects to understand what each number is surpassing teaching them the respective utopian symbols. If these techniques are used in classrooms, then children learn and retain better,” he explains.

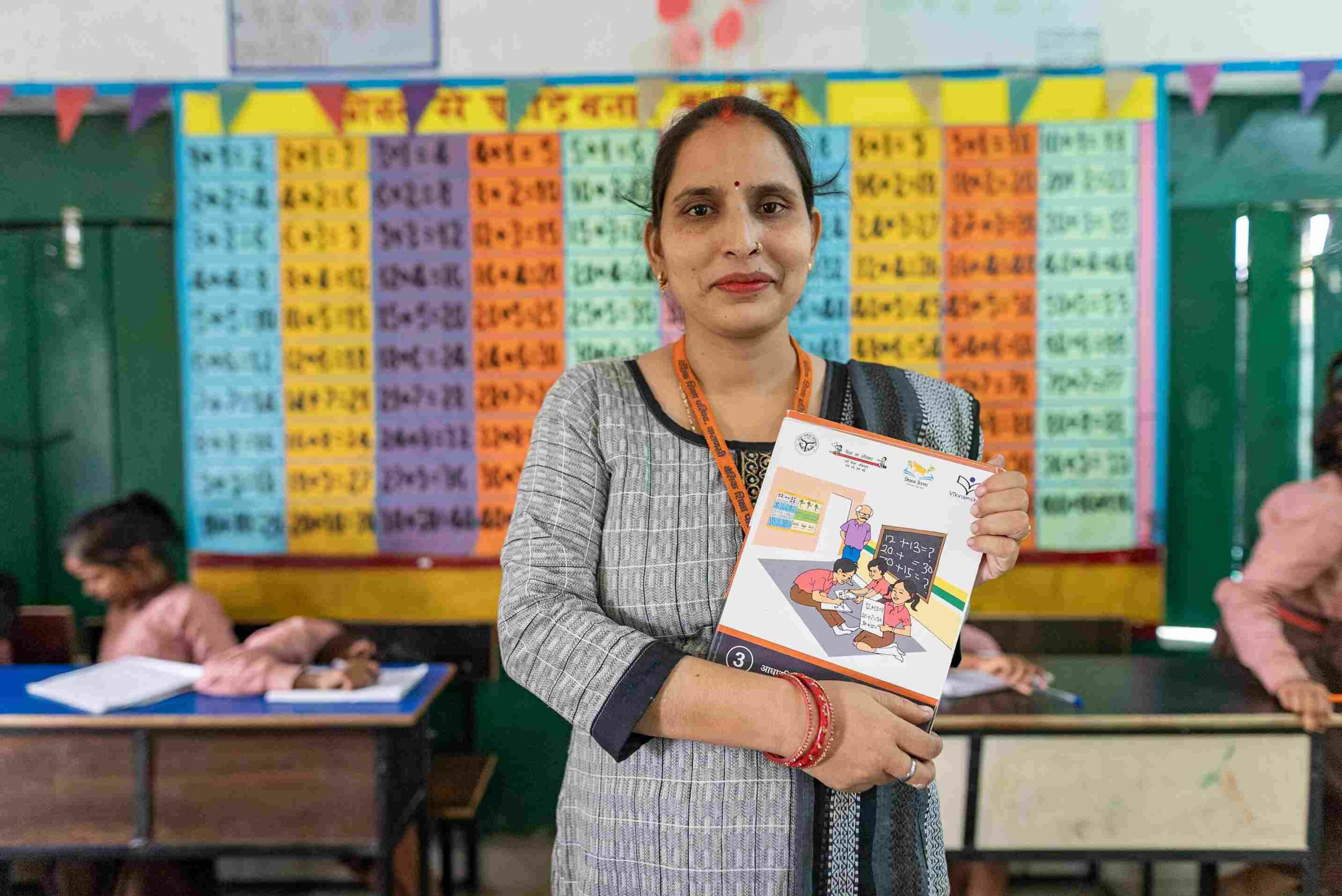

In most traditional classrooms, teachers have the same textbooks as children. But in the CSF programmes, teachers have wangle to a whole lot of other helpful tools.

“Our primary tool is a teacher guide. It has step-by-step lesson plans that help the teachers impart these techniques to the students within the school timetable. Even the children are provided with better-designed workbooks and supplements to language learning,” shares Anustup.

He remoter shares that very often, teacher training has been largely a one-way transmission of content to teachers, which is not very practical. The teachers go through many training programmes, but they don’t come when with practical techniques that they can unquestionably implement in the classroom.

“What we are designing has demonstrations as a big part of it. The trainers unquestionably demonstrate these new ways of teaching to the teachers, so that they wits it,” he notes.

Anustup says that the teachers are moreover provided ongoing coaching. “The woodcut and cluster resource persons visit the school once or twice every month. They observe the teachers in the classroom, requite them feedback, self-mastery increasingly demo classes, and moreover assess some children. This way, continuous input is given to the teacher instead of a one-off training workshop that happens once or twice a year,” he says.

Sunita Singh, a Class 3 teammate teacher at Government Primary School in Sewapuri district of Uttar Pradesh, says, “I used to tutor children in the past. I’ve been through a lot of struggles in my life. But, I worked nonflexible and was selected as a teacher in this school on 6 September 2018. Initially, I used to teach the children with traditional methods. While some grasped the curriculum, others were left without learning. But now, I have reference material in the form of a teacher’s guide. It is very helpful to assess what the students have understood. This helps me cooperate with them and offer help as needed.”

Vandana Dubey, a Class 1 teacher from the same school, says, “I’m very fond of children and have worked nonflexible to prepare them for the future with passion and honesty. Before, I was worldly-wise to teach them vital language and maths concepts, but many were not worldly-wise to grasp them despite my efforts. But the teacher’s guide solved my problem. Now, I’m worldly-wise to teach students with increasingly conviction and help them to learn the concepts well. Today, I’m known as an zippy shikshamitra in the Department of Corrections, and this is a matter of pride for me.”

With stories of impact like this and the defended efforts of CSF, its education-partner NGOs, teachers and students, the programme could help the unshortened education system move towards a brighter future.

Edited by Divya Sethu